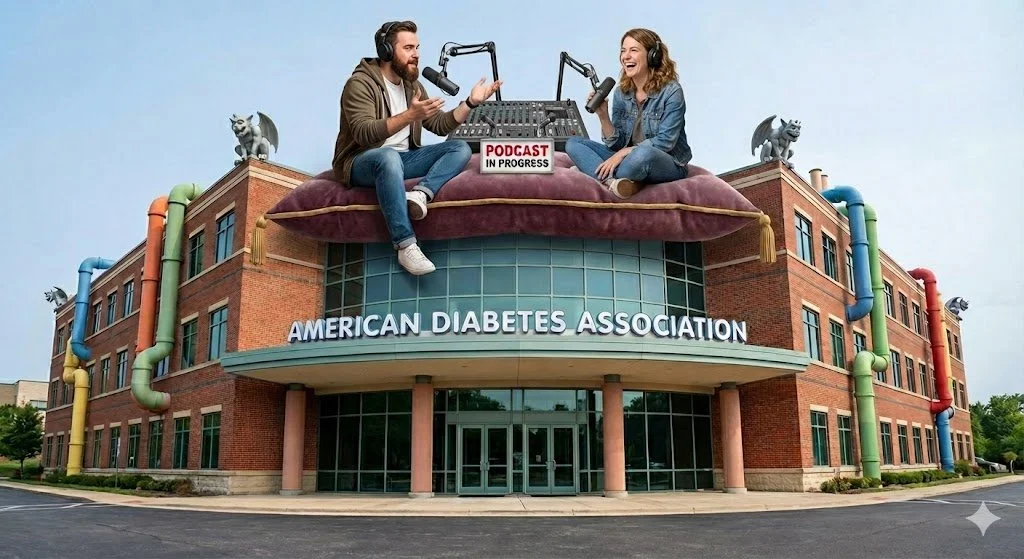

#490 More Julia

Julia is back!

Dr. Julia Blanchette, PhD, T1D

You can always listen to the Juicebox Podcast here but the cool kids use: Apple Podcasts/iOS - Spotify - Amazon Music - Google Play/Android - iHeart Radio - Radio Public, Amazon Alexa or wherever they get audio.

+ Click for EPISODE TRANSCRIPT

DISCLAIMER: This text is the output of AI based transcribing from an audio recording. Although the transcription is largely accurate, in some cases it is incomplete or inaccurate due to inaudible passages or transcription errors and should not be treated as an authoritative record. Nothing that you read here constitutes advice medical or otherwise. Always consult with a healthcare professional before making changes to a healthcare plan.

Scott Benner 0:10

Hello, friends and welcome to Episode 490 of the Juicebox Podcast today a returning guest, Julia, Julian, I always have big plans about talking about a certain subject, then we have these lovely conversations. And I don't know if we ever get to the subject or not. But Julie's got Type One Diabetes forever. She's actually got a long list of what they might call the bone a few days. You'll hear in a second. And anyway, she's cool. And this is a great conversation. I probably should have said Julius back. I like Julia, we have a great time talking. Here it is. That is what I should have said. There's too much talking in the beginning. All right.

Please remember while you're listening that nothing you hear on the Juicebox Podcast should be considered advice, medical or otherwise, always consult a physician before making any changes to your health care plan. We're becoming bold with insulin.

This episode of The Juicebox Podcast is sponsored by Omni pod makers of the Omni pod tubeless insulin pump. It is also sponsored by touched by type one checkout touched by type one at touched by type one.org or on Facebook, and Instagram. And while we're at it, I'd like to remind you about the Contour Next One blood glucose meter. It is my favorite meter, the bestest one I've ever held and used, it is super accurate. You'll love it. Contour Next one.com forward slash juice box.

Julia Blanchette, PhD 2:01

I am a Diabetes Care and Education Specialist registered nurse. And I have my doctor philosophy or PhD in nursing science. All right.

Scott Benner 2:13

And you've had hype on For how long?

Julia Blanchette, PhD 2:15

And I've lived with type one actually, for 21 years. I just reached my anniversary last week. You

Scott Benner 2:22

know, well, first of all, congratulations. And secondly, you know you can pass me because you look younger than you are even though you're not old.

Julia Blanchette, PhD 2:30

Yeah, I mean, everyone's always said I've looked younger than I am. So it My mom has good genes. You know,

Scott Benner 2:36

you're in your early 30s, right? No, no, wait a minute. How old are you?

Julia Blanchette, PhD 2:43

I'm in my late 20s. Oh,

Scott Benner 2:46

I like how you made that distinction. Like I'm getting old. So Scott, I'm 31. I'm 29. It's a huge difference when you really think about

Julia Blanchette, PhD 2:58

I'm actually 28. So,

Scott Benner 3:00

okay, so well, then that begs the question. How are you so accomplished at 28?

Julia Blanchette, PhD 3:09

Yeah, so I think a lot of it goes back to my personal story and my own experiences living with Type One Diabetes. And when I was diagnosed, we didn't know anyone with diabetes. And you know, at the time, there wasn't a lot of social support on the internet, because it wasn't really a thing yet. I don't even think Google existed when I was diagnosed. So we actually met a lot of local families who we are still in touch with. And we had a great support system, through kind of the families that we knew from town and then also just from our family, friends and from my friends, and they really lifted me up and I saw the power of community come together. That being said, I didn't have a very traumatic diagnosis. I wasn't very sick. Obviously, my parents thought I was very sick because they didn't have a child with a chronic condition before that, but I wasn't NDK when I went to the hospital is more just to learn how to manage diabetes than to treat me for something really critical. So and then coming out of that I was kind of put into a situation with a great support network. And then from there, I you know, my parents were really supportive in a way that worked on they really encouraged independence, but they weren't pushy about it. And I think I kind of just took everything on myself as I was ready. Don't feel like your child has to do this. I think that part of that is innately who I am. I think I'm a pretty like I want to do things I I get really interested and passionate about things and want to learn how to do them and learn how to help other people and so that kind of led me to my career. career path. So, when I applied to college, I, I didn't know if I wanted to be a nurse because I wasn't thinking I wanted to be a bedside nurse, I really wanted to be a Diabetes Care and Education Specialist like the nurse practitioner that took great care of me and really empowered me to not let diabetes get in my way. And it's really live a normal childhood that my mom and dad provided me. So when I applied to college, I kind of I knew I wanted to go into healthcare, but I wasn't so sure I wanted to go into nursing at first because I knew I didn't want to be a typical bedside nurse. And I knew I'd had to have to go through all that training. And then I knew that the path to becoming diabetes current education specialist wasn't going to be really direct. Like, I know, I may have to take on other jobs in order to get there, you know, turns out Oh, sorry,

Scott Benner 5:56

no, no, let me say that I think it's interesting that we, how we sort of sometimes judge people, right, like this idea, like, this one's not trying hard enough, or that one doesn't want it enough, instead of just saying, some people just aren't wired that way. Right. Like, as you're talking, you wouldn't even know this about your I mean, maybe you'd know it about yourself, but I don't think you'd recognize it, as you heard yourself explaining your life. But you're obviously going to just be kind of balls to the wall, no matter what you do. And that you were, you know, kind of lit up by somebody who helped you at one point and made a decision to go in that direction to help other people. That's, that's amazing. But what I'm saying is, I think that if you if you would have been 12 years old, and gone to the library and been like, this is the most magical place, you'd be the most accomplished librarian in your town right now. Like, like, I don't mean, like you, you have that thing. And, and while that's laudable, and amazing, and the world needs you. I think that if your kid is somebody who gets up in the mornings, like, I want to draw pictures and walk around outside and look at the sky, you can't look at them and say, I wish they were more like this person. I think they're just who they are. And the reason I bring that up, is because I think that that translates into how people manage their type one. And I've been around people long enough just on the periphery, to see that I don't think there are motivated people who really care about their health and unmotivated people who don't care about their health, I think they're just different ways people's brains work. And that applies to everything, even when it's something as serious as diabetes, but I think

Julia Blanchette, PhD 7:38

you nailed it. No, you totally nailed it. I think, like even thinking about the difference between me and my brother, like, he's kind of he's artsy. He's, he's a jazz musician. And I think growing up, like I was very driven with academics. And, you know, you might call me type A, and I think he, you know, he was very not, and I think, if he were diagnosed with diabetes, and neatly, his management style will be a lot different than mine. And that's okay.

Scott Benner 8:07

No, no. And I think it's funny, too, when we hear type A, I think it probably lights up to different parts of people's brains, either you hear typing, you think, Oh, that's a person who's going to be successful at what they do. Or you hear type A and think, Oh, well, there's a crazy person who's going to go to extremes and ruin their lives focusing on minutiae.

Julia Blanchette, PhD 8:26

I'm a Type A not to be typing.

Scott Benner 8:31

I know like you hear people say sometimes, and it always comes off wrong, but I don't think we hear it correctly. I'm glad child a got diabetes and not child B, because child B wouldn't have handled it. Well. I think that's taken wrong. Nobody's nobody's wishing diabetes on child a in this scenario. They're just saying, for as hard as this is, and as well or not. Well, as this is going right now, if the other one got it, it would have gone worse, because they know their personality.

Julia Blanchette, PhD 9:03

Yeah, but I think if you look at it from a different angle, it could have gone differently, right? So someone like my brother, he's not super Taipei, so maybe it wouldn't have impacted his life in the same way. It impacts me, but maybe he would have found other ways to manage like, you know, he uses music as an avenue to kind of keep himself mentally healthy. And so I just think everyone's different. But I'm glad you brought this up. Because this is so my first summer working as a nurse a diabetes camp was what I realized that not everyone had the same diabetes experiences me and when I really my eyes were really open to see that everyone had a different self management style, and different support resources. And that's actually what drove me to apply to do my PhD was when I saw all those differences. And I saw that my experience was so different and that I realized that I Wanting to dedicate my life to this and learn about how to help other people who had greater barriers than me.

Scott Benner 10:08

And I have to tell you that I'm very focused on this to sort of behind the scenes because and he doesn't come up very frequently on the show, but my friend Mike is passed now. And he was diagnosed with type one when we were like 19, or 18, somewhere in there. And he was just a voracious passionate reader. He liked photography, art, you know, he wanted to see cinema, he wasn't, he didn't care about making a lot of money. He wasn't looking to dominate a business, he wasn't trying to be a millionaire. He wanted to get up in the morning, enjoy other people's artistic endeavors. And, and, you know, try to add to them himself. But mainly, he was happy to take in other stuff because he wasn't a voracious reader, like today, I'm going to learn about how, you know, a fulcrum works. He's he wasn't going to read a 300 page book on, you know, engineering, he was reading for pleasure, he was reading for escape, you know, and this was him Well, before. Well, before diabetes, he was always a kid talking about comic books back when nobody talked about comic books. And and he was just a good guy. He was bright, and he was articulate and caring. And when he got diabetes, it wasn't something that he was going to be able to pick apart on the level that I picked it apart, for example, but it doesn't mean that he should have had to pass before he was 50. You know, and I understand that when Mike was diagnosed, it was, you know, regular and mph, and you know, he didn't have a meter and nothing was the same as it is now. But still, I don't know that physicians don't sometimes look at people and go, Oh, well, they're just not going to do as good of a job. And I guess that's what that is. And and I don't think that has to be the case, necessarily.

Julia Blanchette, PhD 11:58

Yeah, I mean, I try to I mean, I don't try. What I do actually is I don't, I don't really look at someone's going to do worse than someone else. Like, I really try my very best to make sure that everyone has adequate resources, and they're given a chance. And I think a lot of times you kind of have to meet people where they are, which may be at a different place. And you really have to consider their life and their factors and figure out how to best support them. And I think Not everyone gets that.

Scott Benner 12:27

No, I agree with you. It's a it's an overused phrase, meet someone where they are, but its intention is, you know, is just as good as saying, you know, when you know, I hate it when people say I think outside of the box. I'm like, if you did you wouldn't say that, but I hear what you're getting it. But no, but I mean, I don't know how else to No, no, no, I agree with you. Yeah, yeah, like meeting someone where they are just means you know, you don't you don't approach a you don't approach a five year old and try to explain calculus to them, you start with what they can take in and, and it's hard to think about people that way during a medical situation, but some people are going to walk into a doctor's office and not have either the capacity, the desire the drive, or maybe even the knowledge of how important it is to apply to when somebody says you Hey, I see you're spiking every morning, tell me what you're eating for breakfast, and you're having three things that compete with insulin, all in different ways. You know, you're having a cereal bar, which is going to hit for forever and hard. And then you're mixing in some sort of like fruit juice, which is going to hit you really fast and spike you up at something and you've now mixed in every difficult food into one thing. And your blood sugar jumps up to 200 it stays there for a while it comes crashing back down. You stop it with some juice, you overcorrected, it goes back up. How many times do I have to tell you, you can eat that for breakfast? Or you have to thoughtfully figure out how to put the insulin in? And how many times do I watch you not do it or not be able to accomplish it before as a practitioner, I think well, I guess this person's just going to do this in the morning. And they're not, they're not motivated to change.

Julia Blanchette, PhD 14:12

And that's where I come in as I show them the data and kind of help them figure out okay, if you really like this cereal, how can we eat it? In a way that won't spike you as much?

Scott Benner 14:23

Yeah, well, but you know, the problem is, and this is off track already, all of our conversations are gonna end up being but um, but I can Bolus for those things. I'm sure other people can too. But there's so many considerations along the line, you have to have a real confident understanding of the insulin so that you're not afraid of it and all this other stuff has to happen. And then then then the X Factor is of course they don't eat it in front of you. So they're doing things that are impacting the outcome that they don't know are impacting the outcome that you can't see because Cuz you're not with them?

Julia Blanchette, PhD 15:02

Yeah, yeah, it's, it's tricky. And I think, with a lot of providers, like, if you don't have time to actually help the person with diabetes, think about all the factors, it's really hard for them to then understand how to make changes. I've helped

Scott Benner 15:17

to separate people in the last 10 days. One of them listened. Wow, one of them is listening, sort of, and you can see it on their graphs. And I don't know how to tell the second person, if you would just stop thinking for five minutes and just listen, this would be okay, you'd see it be okay. And then you'd learn how to mimic it. But they're, they fight against it. It's, um, and I don't mean to fight in like a adversarial way. I mean, that I again, I think they're doing something they don't realize they're doing, it's having a big impact. And because I can't be with them, I don't know how to, I don't know how to stop them. You know, long enough, you know, how like, sometimes when, like, a kid freaks out, sometimes you have to just go like, Alright, everybody stop. Everybody stop. We're gonna start over again. I feel like people's management is like that sometimes. Like, it's like a kid that's out of control. I was gonna say tantruming. But I don't mean it like that. I mean, just like there's craziness and yelling and arms flailing and, and, and sometimes you just got to stop, you know, you have to stop and start over and try to see the bigger picture. I don't know. Well, alright. Julia, I don't know how that happened. You know, I got interested in something that you said. And then I was like, Oh, well, that's got nothing to do with why she's on. But that's interesting. We're gonna talk about two simple things today, I think that are very difficult, but simple questions. And they're questions from the Facebook group, the private Facebook group. A first one is, how do I manage a kid with type one, so they don't also suffer from depression, anxiety, eating disorders, stuff like that? And what do I do if these things happen anyway? So how do you talk to people about those issues? And can be avoided?

Julia Blanchette, PhD 17:09

Yeah, so this is definitely a long conversation, it's not going to be a boom, boom, boom, answer. Um, yeah. So that, you know, people with diabetes, children, adolescents, young adults, adults have a higher risk than the general population of anxiety and depression. And then those eating disorders typically emerge during the adolescent young adult years, which were also at higher risk for. So why do we have such a high risk? So you know, a lot of living with a chronic condition and the extra stressors, definitely contribute to an increase in risk for those mental health comorbidities. But if you go to the roots of it, so you know, there's some people and we were kind of talking about this before that are innately more prone to anxiety. So that's kind of in its own bucket, right. And so, example, like, I'm innately more prone to anxiety, like I have anxiety at baseline. That being said, the anxiety I have isn't particularly related to diabetes, it's related to other things. So somehow, I somehow it doesn't relate to diabetes for me. Um, but I am ready. Right? Isn't that crazy?

Scott Benner 18:23

Is it a driver in your type A personality?

Julia Blanchette, PhD 18:26

Yeah, I'm innately more prone to that anxiety. And I think so what I was about to go into, though, is I think a lot of it has to do with your diagnosis story, right? So I didn't have a traumatic experience. And then I was surrounded by a great level of support and encouragement. And people that lifted me up and helped me feel normal and gave me a sense of normalcy. And my providers increased my self efficacy and self management skills and confidence. And all of those factors are protective against anxiety and depression related to diabetes in a young child, right. So I had resources I had support at the time, my family functioning, was, was high and we were banded together, changed later down the road. But, you know, family functioning in itself contributes to the risk of anxiety and depression in kids with diabetes. And, you know, I really just had that stable support system. And I didn't have a traumatic diagnosis. Now had I had a traumatic diagnosis, the best thing would have been to go right to get psychological help. And I think a lot of the pediatric diabetes clinics as part of their standard care do have the family meet with a pediatric psychologist at diagnosis, and I think that's good practice because, you know, like a kid adjusting to a new diagnosis and changing what's normal can induce a lot of anxiety. So I think that's something that everyone should do if you have the chance to do it. Now that being said, I think anything that's new and different, can definitely lead to those feelings of anxiety and depression. Right. But depression, I think comes with our from the burden. And the burnout related to diabetes. Sometimes it'll happen at diagnosis. But that's usually more for like young adults and adults, it could happen with kids too. But I think with kids, we see more of the depression happening and like the adolescent, young adult years related to just the burden of diabetes, and being different, and having to deal with this and having those blood sugar swings that can also contribute to feelings of depression. And so I think that answered part of it, I have a few factors. One, I

Scott Benner 20:51

want to ask a question. So yes, do you see outcomes? Driving burnout? Like, do people who have amazing, are there two different ways to burn out? I guess, is my question. So let's say that, like someone has the outcome they want more often than not, right? Whatever it is, they're they're aiming for. And does that person get tired of diabetes less than a person who has crazy variability that feels uncontrollable, and everything feels like it's not within their power to affect.

Julia Blanchette, PhD 21:29

So Person B is going to be more prone to getting burnt out. But Person A can definitely get burnt out too.

Scott Benner 21:35

So when you lay right, in focus why,

Julia Blanchette, PhD 21:39

yeah, like, if you don't know how to how to manage your diabetes, and you don't have resources, and you feel like everything's out of your control, that's out of control feeling is going to lead to burnout. But then sometimes you can get, you know, tired and just emotionally at your capacity when you are really intensively doing something like the other type of person that you describe. So it can go either way. But doubly the person that doesn't have the tools, or understanding will have probably have a greater chance.

Scott Benner 22:15

I just wrote a note for myself, because I just found myself thinking that I want to talk to Jenny too, about what it feels like for her when she burns out. Because I if she does, because she appears to be the kind of person who's just got a good disposition. I don't even know how I mean that exactly. But I don't think Jenny gets down for long. But I'm wondering if I'm wrong. And I want to and now I want to find out because if she experiences that, then everybody's going to because she is amazing. At her outcomes. She's She's not burdened by her meal choices, like she's not getting up every day going, Oh, I can't believe I have to eat this. Like she's happy the way she eats. And she understands how to use her insulin. So I obviously I mean, you've listened to the podcast for a while. Yeah, I believe that if you understand how to use insulin, you'll have more frequent stable outcomes. And that'll make things easier for you. I wonder if I don't not think about it as burnout. Because I don't have diabetes, I think about it as aggravation. Like, well,

Julia Blanchette, PhD 23:20

so if you're if you're someone like me, or Jenny, I'm gonna grip myself with Jenny because I, I find that I'm exactly what you just described, like, I'm happy with what I eat. You know, there are times when I get frustrated, like if my blood sugar's higher than usual, and that come down like, yeah, that's frustrating. Yeah, um, but for the most part, I knock on wood, I've never gone through a period of burnout with diabetes. And I think a lot of it is because I, I do understand, and I'm not hurt on my sleeve, even on you know, we have a bay, but I'm not hard on myself with diabetes, because you can control what you can control. And you do your best, and you understand what you understand. And you try to minimize the fluctuations and patterns, and that's your best. And so to me, I don't get frustrated when things go slightly wrong, because they're going to go slightly wrong sometimes, right? If I have a bad site, for example, or if I miss count carbs, and that to me, that's, that is what it is. We're not perfect. But I do think the people that seem to get burnt out, are also people that I find a lot of times they're putting in way more effort than they have to be because something else can be changed.

Scott Benner 24:34

Okay. I okay. So they're working hard. It's like they're beating their head against the wall. They're trying Yeah, the wrong things. They don't realize that they think they're the right so that's my other thing, but you were talking about like getting frustrated about at a high blood sugar. And even that can be dependent on your level of, I think knowledge and skill around using insulin because if a blood sugar appears to just magically get high. That's one frustration, right? That's a frustration that there's magic happening that I'm unaware of and don't know how to control and it's causing this blood sugar.

Julia Blanchette, PhD 25:12

Now, I don't believe in magic. Right,

Scott Benner 25:13

right. I don't either. But I think that's how people feel about it. Let's the diabetes, Carrie has decided your blood sugar is going to be high, right? But instead, that's not why like you. Listen, I'll say it here. And I mean it, I'll defend it anywhere. If your blood sugar is too high or too low, you're using insulin wrong. That's it. And so it there's no more or less to it than that. Yeah. How do you how to use it correctly? There's a lot to but at it's good.

Julia Blanchette, PhD 25:39

I think what I was trying to get at is even like someone like me, and I bet Jenny will admit to this too. Like, I'm not 100% enraged with a flatline all the time, I'm close, but I'm not, you know, I have there are things that I do that I want to do. That'll vary my blood sugar a little bit sometimes. And I just, I don't get frustrated with it, because it is what it is. Does that make sense?

Scott Benner 26:01

Oh, no, it doesn't mean it. 100%. And I agree with you. I don't. I know there are people who feel like it's it that they want to keep their blood sugar at 83 for their whole life. And there are ways to eat the keep it that way. Like you can I'm

Julia Blanchette, PhD 26:14

not that person. Like I understand the science behind it, you know that? You know, there might be people that listen to this that have a different viewpoint. And I understand that. But from my standpoint, there's no point in me trying to lower my agency, like I'm already at a level where I feel is low enough. And that I don't put in a huge amount of effort to get here. And so I'm like, why would I put in more effort to get lower when the data is showing that I'm not, you know, I'm not varying. And my risk of complications with this agency is a one C and really time and range, right? And my variability is quite minimized. So why would I try to make it flatter? Yeah, kind of how I feel. Oh, yeah,

Scott Benner 26:55

I'll give you an example. I just have to open up this app. So Arden's blood sugar right now is 120. It's been addressed, okay, like it's it's we've dr address the 120 with the same you know, veracity that somebody might address a 300 I'm like I have that I'm going to make that 85 again, but looking at Ardennes I have Arden's last seven days here, estimated a one c 5.4. Standard Deviation 30 codo coefficient of variance 28. And an average blood sugar of 107 Arden's a one C has been in the mid fives for years, it's been between five, two and six, two for like seven years now. And right now she's in class. You know, she's in her bedroom in front of a laptop, but still, she's in class. And something clearly happened that made her blood sugar go up a little bit. And I'm not going to over Bolus a 120 and cause her to have to have carbs a half an hour from now. So that the 120 only exists for a half an hour instead of an hour. Do you know what I mean? Like I just that seems okay to me, like I've seen my own blood sugar, and 120 happens. You know? So I think that in the pursuit of stopping a 300 there's this anxiety that comes as soon as you see the blood sugar going up. It's gone to 300 so many times, you're just like, oh my god. Oh my god. Oh my god. If it ever goes up, it's definitely gonna go to 300 but we don't live in that space. Arden's insulin is set up in such a specific way that it's nearly impossible for her blood sugar to go to 300 unless something radical happens like our pump gets knocked off or like something like that.

Julia Blanchette, PhD 28:46

But you know what? I've even noticed when my flight gets delayed when I was actually I can't hear

Unknown Speaker 28:54

you hear me now? Try again.

Scott Benner 28:55

You even noticed when your sight Do you hear me? No, no, you're really low. Hold on. That could be me. It is me. It's not you.

Unknown Speaker 29:04

Hear me now? Give me one second. There's a setting in here that I have to why does it want to do that?

Unknown Speaker 29:13

That is unpleasant.

Scott Benner 29:18

Hold on one silly Second. Okay. All right, got you even

Hey, check out touched by type one.org. They're a great organization doing absolutely astonishing things for people living with Type One Diabetes. They're a touched by type one.org. You can also find them on Instagram, and Facebook should check them out. They're not asking you to do anything but check them out. It's a super simple ask you're on the internet all the time anyway. I mean, how many times can you find out what Prince Harry's new baby's name is just touched by type one battle?

Now when you're done with that, we're going to head over to the Omni pod website, it's at Omni pod.com forward slash juice box. And there you're going to find out if you're eligible for a free 30 day trial of the Omni pod dash. Now listen to what I just said, you're going to use an insulin pump for free for 30 days. So that could be you know, you use a different pump now and you want to try the Omni pod but you don't want to, you know, make the full commitment. That's cool. Try it out. Maybe you just want to see what it's like to swim tube lessly this summer? Hmm. tubeless swimming. It sounds intriguing, doesn't it? On the pod comm forward slash juicebox maybe you're using the the needles, the injections, the pens and you think to yourself, I hear about these extended boluses and I would really like to have more control over my Basal insulin Omnipod comm forward slash juice box? It's a tubeless insulin pump. Are you kidding me? You got to go check it out right now. I mean, moron, there's no tubing, no infusion set that runs through a tube that runs through a controller. That's right, Scott, that doesn't exist with the Omni pod. Now, last thing, and this is important. The Contour Next One blood glucose meter. You can look at that with your eyes on the Internet at Contour Next one.com forward slash juice box. Why would you do that? When you probably already have a blood glucose meter? Well, I have some pretty clear thoughts on that. And I'm going to share them with you all right now, the Contour Next One blood glucose meter is the most accurate meter My daughter has ever used. That is first foremost simple. It's easy and obvious to understand you probably don't even need to listen anymore. You just head to Contour Next One comm forward slash juicebox right now, but if you want to know more bright light for nighttime viewing, easy to read screen for the number thing like right, yeah, look at the beep and then the number comes up, you want to be able to read it, you can. It's simple to hold an easy to use. It's intuitive design. You know what I mean? There's an intuitive design to it. It's not clunky or weird or like a big teardrop or something. It fits nicely in your hand in the orientation that you use. When you're testing. I know that might sound like way too deep dive on a blood glucose meter, but it's not grabbing your hand it's kind of like a pencil thing. Boom you go you'll see it contour next comm forward slash juice box. It also has Second Chance test strips. So you can go into that blood, get some but not enough head back get the rest without wasting a test trip or impacting the accuracy of the test. Two big deal. Contour Next one.com forward slash Juicebox Podcast meter I've ever used. Why are you walking around with that junky meter in your pocket? in your pocket book in your bag? Did you even ask for it? Or did the doctor just give it to you? If someone hands you a meter and tell you that was a meter Did you even look into it? Contour Next One comm forward slash juice box on the pod.com forward slash juice box touched by type one.org. Back to Julia.

Unknown Speaker 33:20

Alright, God testing

Scott Benner 33:22

you there. You even you even notice when your site

Julia Blanchette, PhD 33:26

like when my site is bad right now, I will go up to like, I'll start I'll start seeing myself creep up like, you know, above 180. And I know something's wrong. And I'm at the point where if I get into the mid to hundreds I feel disgusting. Like disgusting. Yeah, from a bad site like and it ruins my day. So that that is a point of burnout for me like I had a period a few weeks ago where I had a bad box of infusion sets. And it was kind of dramatic, because you know, I, you know, I train on all the pumps and everything. And I have resources. And I was I tried a couple different boxes. And that was a little frustrating. But even that, like I'm more felt frustrated because I didn't feel well opposed to feeling super burnt out.

Scott Benner 34:07

Well, that is something I didn't bring up that I meant to a little while ago because you alluded to it, you know, when your blood sugar goes up and you're aggravated. You do have to see if you're an aggravated caregiver or an aggravated person with Type One Diabetes. You both have different stressors and aggravated caregivers worried they're hurting. They're the person they're caring for. The person who has diabetes is going to feel unwell because their blood sugar is high, which could lead to aggravation and does.

Julia Blanchette, PhD 34:35

Yeah, and I think it's so important for caregivers and I'm not a caregiver, right. So this is just speaking as someone with diabetes who works with caregivers and people with diabetes, but I think my mom is not an angry person and was always supportive and compassionate. When my blood sugars were going up and down throughout the years. You know when we had the type of people That didn't even have self adhesive on the infusion site or a Bolus calculator, but that's a different story. But yeah, so even when we had like that type of technology, and I had technology failures, my mom was just sweet and compassionate and supportive. And I think that really helped me. And I think when I'm working with people with diabetes, they don't want someone who's going to yell at them. There's so much shame people come in so afraid and embarrassed to look at their data with me. Yeah. And that's not how it shouldn't be people need support. So I Well,

Scott Benner 35:39

two things. First of all, the next time you speak to your mom, you find out for me, and I'll ask you next time, did she smile to your face? And then run into another room and yell into a pillow? or was she just like that the whole time that I want to know. And

Julia Blanchette, PhD 35:54

she's like, not the whole time, I can verify she's not an angry person. Just it's just weird. It's weird. She's a neatly like this magically, not angry, not anxious person, and I don't understand. Um, so that's who she is. She had tips for coping mechanisms, but I don't think she does. I just think innately she was like, this is how it is. And we're gonna do this. But I mean, I think in a way to she had good support. So maybe that's what helped her through it. I don't know.

Scott Benner 36:23

You don't think she was like in the laundry room? She turned three sneakers in the dryer, turn it on, just yell fuck for 20 minutes. And then No,

Julia Blanchette, PhD 36:29

she hasn't swear. I swear, my mom does not she's like, every time I swear in front of her. She's like, I don't know where you came from?

Scott Benner 36:39

Oh, yeah, I guess so she's all sad. And you're like, all wound tight. She probably like what happened? Okay. Okay, so we, again, this is gonna be a meandering conversation, because I don't have the real ability to do anything otherwise. But so. So support is what you're saying. It's I mean, I feel like what you're telling me is that if you're well supported, you're not the kind of person that flips out and causes more anxiety than needs to be and you understand how to use insulin. These are the measures you take to try to avoid the things that we mentioned.

Julia Blanchette, PhD 37:13

Yeah, and I think when we're talking about support, it supports only so helpful when you don't have the knowledge base and self confidence and understanding and self management. So the two are very important together. But you know, also, there's other factors too, like resources. Just think about when I was diagnosed, I went to Yale New Haven Hospital and had a great pediatric endo team, they gave us all the resources, we needed, all of the knowledge that they had to share with us. If you're in a more rural area, or don't have that amazing diabetes team like that, in itself, can change your diagnosis story and what you're thinking and can impact you. I partly

Scott Benner 38:01

love how the podcast works because of geography and how some people just don't have access to the same things that others do. But I am also thinking that maybe, like, when you when you say you need good support, that probably can seem like pre defeated to people, because what does that mean? Like, you know, if I don't know how to do diabetes, I think people might be thinking that support means that someone else will tell you how to do it, which obviously, you need, but I mean, but I think

Julia Blanchette, PhD 38:33

knowledge, right? I think the other person is more of the knowledge base. I'm talking about, like we didn't know anyone with diabetes. And I can tell you, we had any, you know, this is pre COVID times and everything. I had people coming into the hospital, my friends all showed up at the hospital. We danced around at hospital socks. I had, you know, I we painted our nails, we did puzzles, we read books, like this is what I remember that being in the hospital. I don't remember being scared and sick.

Scott Benner 39:01

Yeah, maybe. That's what I meant is that real support is sort of not as much support as it is the lack of stress. Yes. Like you can support somebody by not adding to their burden.

Julia Blanchette, PhD 39:15

Exactly. And you just need people that you can lean on, right. So part of what made my childhood so normal is that we had people that supported us, and really came together to help our family. But they you know, they also like I went to sleep overs. And yeah, probably that was probably something that made my mom really anxious. But we had multiple family friends that were willing to have me over for sleepovers like that is the type of support that made my childhood normal. That, you know, my mom knew that these people were also willing to help care for me. And they just did what my mom said right? So they didn't necessarily have the knowledge. It wasn't necessarily knowledge. It was just having community support people to lean on people to help us make the situation normal. Yeah. And not everyone has that. But I think what I'm trying to get at is, if you have people you can lean on that in itself can reduce the risk of anxiety and depression.

Scott Benner 40:20

Now, I, Kelly sister would have Arden overnight, and she really just didn't know what she was doing really, but she just took good direction. She's like, so I'll tell her here. Um, well, she was willing to be up at three o'clock in the morning to double check things like she just she was she she was willing to create a place for art and to feel like not accepted but not excluded, I think is the Yeah, right. Cuz she was obviously accepted there. It's when the exclusion comes in. Well, I don't want to get up at three in the morning to check your kids blood sugar, so they can't stay while everybody else stays. It's not exciting people. Yeah, excuse me.

Julia Blanchette, PhD 41:02

And the other thing that really helped me to feeling a sense of normalcy was actually going to diabetes camp. So I think before I went to camp, I did not care to show anyone my insulin pump, I kind of, you know, I felt different, even though I had a great support system. And my friends were very nice about it. And, you know, very supportive about me wearing an insulin pump. I just, I didn't really want to show people I didn't know I kind of covered it up. And so going to diabetes camp also gave me another sense of normalcy and support. I'm like, wow, I'm not in this alone. There's all these other kids like me. So

Scott Benner 41:39

I see Instagram do that for people. Yeah, their ability to just show their pomp or put in their bio. I have diabetes. Like I think that's another form of not hiding.

Julia Blanchette, PhD 41:49

Yeah, no Instagram, though. Did you say Instagram you got cut off?

Scott Benner 41:53

I did. Yeah, I just mean a place a place where someone can go out into the world, whether anybody sees it or not, and say, Look, my CGM is on my arm. It's okay. Like, this is a normal picture of me and my friend. And I'm not hiding this thing. It's not that they're not hiding it is that they're, they're expressing that it exists. And and I don't know, like, I also see the value for some people not telling anybody I understand when adults tell me they don't want their Boston or they have diabetes, I get that. Well, that's a different, but that's a different stressor. Yeah,

Julia Blanchette, PhD 42:25

yeah, that's a different totally different situation. It's you don't want to be judged or treated differently, or, you know, not given the same opportunities in the workplace because of it, right?

Scott Benner 42:36

That it's different than just saying, hey, world, look, I have a insulin pump on like, that's not the same thing. But still, they I get we're going to diabetes camp is just fine. You're in a place where literally nobody can hide that they have diabetes, you need to have it to get in. So

Julia Blanchette, PhD 42:56

yeah, yeah, exactly.

Scott Benner 42:59

We don't like kids come here, don't have diabetes, we all have it. And then that, that's just one consideration that's gone. I ever everyone knows, and, and maybe everyone's experience isn't the same, but at least there's, we have a baseline that we all share, I guess

Julia Blanchette, PhD 43:16

I actually think diabetes camp opened my eyes to so many things. So I need friends from all different backgrounds like camp, and that to this day has really shaped who I am. So just a little shout out to diabetes camp camps, in general, really teach kids a lot of skills that you don't get otherwise. So I benefited from camp in general. Um, you know, from my own development standpoint, but also, I grew as a person with diabetes, when I first met more people my age with diabetes

Scott Benner 43:50

camps a funny thing, because I think people have one of two very distinct and different reactions to it, either, it seems exactly the way it seems to you or other who were like, Oh, I am not doing that. And I don't, I would never want to do that. Like I just it's, I think there's there that falls into two basic factions, like you're either this is a great idea, or Oh my God, I cannot think of anything worse than going to a place with a bunch of people I don't know, and sleeping in a cabin with them for two weeks. I

Julia Blanchette, PhD 44:17

was really scared. I was really scared. I actually used to not be an outgoing person at all. And it did freak me out. not lying. Um, but I think it made me more comfortable and kind of helped me connect with people in a different way. And it took me out of my comfort zone and I think that's what helped me grow. Yeah,

Scott Benner 44:39

no, I listen, I'm not saying there's a right or wrong. I'm just saying I think there's a reaction to the I don't even mean diabetes camp. By the way. There are people like you. Oh, yeah.

Julia Blanchette, PhD 44:46

All sleepaway camps. Yeah.

Scott Benner 44:48

If you told me when I was 15, that I would expand myself by going to a summer camp. I would go. I'm not doing that. And that would be the end of it right there. I don't there's nothing about that. that strikes me as a good idea. And I'm not discounting how amazing it is for other people at all. I'm just saying that for me personally, it doesn't. It doesn't make any sense. Okay, so I guess I guess I'd like to know, too, and it feels like it fits in here a little bit. How do I recognize the eating disorder as it's approaching?

Julia Blanchette, PhD 45:24

Yeah, so I actually didn't even have a chance to go into like, the risks for eating disorders and diabetes are a little bit different than anxiety and depression. Why I didn't do much, or Yeah, yeah, I have, yeah, I have some time. Um, I don't really have time, but I have time for you. So. Um, so with eating disorders, you know, someone who is more prone to anxiety innately is at a slightly higher chance of an eating disorder. And then any trauma, like a traumatic diagnosis, or any type of like family trauma, or any type of trauma can also contribute to all of those mental health disorders, and increase the risk for an eating disorder. But with diabetes, eating disorders are actually more prevalent than in the general population, because part of diabetes is this focus, there's two things one is the focus on managing your blood sugar's and trying to keep them in range, when, you know, it's not super easy for everyone to do that not everyone's given all those tools, right. And especially for someone who really wants to control everything, like that lack of control is what really can contribute to the development of an eating disorder. So I think, you know, this will prevent all eating disorders, but if you give your kids just the ability to feel like they're in control some way of their life or their diabetes, I think that may, um, you know, help prevent eating disorders slightly. But that being said, if somebody is really fixated on trying to control their blood, sugar's you know, in a certain range, and perfect it and they can't, that can contribute to controlling weight, controlling something, which would be what you eat, or what you put into your body. And the other thing with diabetes, that contributes to a high risk of eating disorder, higher risk of eating disorders, is just the fixation on everything we're putting in our bodies, right? So the fixation on all of these foods and how they impact our bodies in the carbohydrate content and counting, everything like that can also contribute to a higher risk of eating disorders. And I left out to just the, the feelings that you're not normal and discomfort with your own body because of diabetes is also something that contributes. So there's all those factors, in addition to all of the other psychological barriers and factors that can increase the risk of psychological distress and mental health diagnoses and people with diabetes. So with eating disorders, that's kind of what contributes to them. But the signs and diabetes, you know, are unique, because we have more data to look at. So, in particular, one of the biggest telltale signs is frequent decay episodes, consistent high blood sugars, omission, or not giving insulin, particularly at meals, eating carbs, I'm covered. I mean, some teams are gonna eat carbs, I'm covered, but it's more of like a behavior where you physically can't get yourself to give insulin to cover the carbs because you are trying to keep your blood sugar's higher. So some of those are kind of more in line with diabetes aimia. But, you know, there are people with type one that also have anorexia and so with that, you might see more low blood sugars and those lows might not come up the same way that they would in somebody with glycogen stores. So anorexia, I mean, not to like freak anyone out, but anorexia can be very dangerous too. with diabetes in addition to Dibley, Mia and I think we focus more on diabetes, Lamia, but anorexia is out there too. And the lows

Scott Benner 49:19

are you saying because with the lack of any kind of food in your body or the the the regurgitation of the food, your body doesn't have the ability to store glycogen either. So when you get low, the your liver can even help stabilize your blood sugar. Is that what you're saying? Yeah. Oh, that's frightening.

Julia Blanchette, PhD 49:39

That's great. So yeah, so PSA, if you know anyone who has diabetes and anorexia, if they do go very low, glucagon may not work. So that would be a situation where you have to give dextrose or glucose IV dextrose. If they're unconscious, I was fortunate.

Scott Benner 49:58

I saw someone give Luke had gone on, like they were talking about their low blood sugar incident. And they use glucagon a number of times. And I was like, I don't think they understand how this works. Because they put it in, you put it in once, and your body releases the stored, you know, glucagon. But you're putting in more doesn't it? You're the stuff in the needle isn't the stuff that makes your blood sugar come up this stuff in the needle is the stuff that releases the glucans. And, and that stuff I know, I'm not speaking Technically, the point is using three glucagon is it's no different than using one glucagon. But, yes, I watched this person make that mistake. And this was not a new person to diabetes, which made me want to bring it up somewhere because it did not, it seemed like something they should not have not understood.

Julia Blanchette, PhD 50:46

So sometimes we recommend to give a second dose. But that's like if you have a lot of insulin in the system and need a greater release of stores. Right. But if it's not working, it's not working. Because there's not you don't have the stores. morbid, but but it is a sign like lows that won't come up like that can be a sign of anorexia as well. Okay, so, um, and then there's just the signs of typical eating disorders to like with exercise anorexia, right. So exercising off more than you're taking in, on can be assigned to Wow.

Scott Benner 51:22

And it's interesting to that, as you're explaining it, the idea of wanting to control something is at the core of all these ideas, I'm either going to eat a lot, I'm controlling that, or I'm going to eat nothing, you're controlling the flow of food, right? And so when so these things come when you when the mind can't find any sense of control anywhere else.

Julia Blanchette, PhD 51:48

Yep. And the other thing too, that I didn't even get into is binge eating, binge eating is really common. in adults, I see it a lot in adults a diabetes, and that in itself, it's you're you, you're trying to control something and then you kind of just eat everything right. And that's part of the stress release mechanism.

Scott Benner 52:11

Yeah, and what is what can binge eating look like? Is it constant snacking? Or is it Oh, no, it's sitting down with a mass of food that not no one should take in at one time and just forcing it in?

Julia Blanchette, PhD 52:26

Well, so a lot of people who Benji will do it in private, like, they're not going to do it in front of others, but a lot of times, they don't eat a lot. And then or they're trying really hard to, um, for lack of a better word, control what they're eating, like, eat, like having fallen kind of like a rigid diet, and then they'll just binge on something. Later on, and the things that people binge on are different based on the person. But um, a lot of times it's in private at home, and I can't even tell you because I I don't do therapy with people who Benji, I just know, I, I work with people's insulin management when they have been eating diagnosis. So yeah, a lot of times it's it's eating a lot of food. And it's a stress relief mechanism. Well, Oh, geez.

Scott Benner 53:24

Oh, see, you're, you're you're like you're very upbeat, everything. Everything you bring up is exciting.

Unknown Speaker 53:31

I mean, I think that was my topic. And

Julia Blanchette, PhD 53:35

I feel like anyone that is seeking help, I mean, I look at it from the standpoint like anyone that's coming to me for help with insulin management that's seeing someone else to help with their diagnosis, like they're doing all they can to take control of their diabetes. And I think that's a good thing.

Scott Benner 53:53

Yeah. So what you're describing that I don't know if it's coming out or not, is that while while a person is off, trying to address their eating disorder with someone, you're actually helping them use the insulin to get through the eating disorder? Is that right?

Julia Blanchette, PhD 54:06

Yeah, I do that a lot, actually. Um, so we had a dietician who worked with me who specialize also in eating disorders. And she left. So I took on a couple of her patients, but even before that, I had some experience from diabetes camp throughout the years, with adolescents who had eating disorders of various types. And then, because eating disorders are more prevalent, and people have diabetes, and in the general population, I do have a handful of patients who have eating disorders. So Wow.

Scott Benner 54:39

Yeah. Well, that's really nice work. It's good work you're doing and I appreciate you coming on the show and talking about this. We're obviously going to try to do this more frequently with you. Yeah, so but I

Julia Blanchette, PhD 54:49

apprec I don't think we really had time today to go into like, how do you handle

Scott Benner 54:54

No, no, I think about 20 minutes into you talking I realized that this is not This is not a to be conversation. This is a longer, you know, chat. These are chapters not not just like, you know, bullet points. Exactly. Yeah. And And not only that, but we had a little technical problem in the beginning, that was my fault. And so we were a little shorter on time than usual. But still, I realized an extra 10 minutes wasn't gonna help anything. This is an ongoing conversation. So

Julia Blanchette, PhD 55:23

we could talk for a long time about it. So I will be here to complete the chapters. And we will

Scott Benner 55:28

that's it. So Julie is just trying to stay on the podcast more. She's like, I'll stretch this out a little bit. Now. It was your idea. I know it was. I'm just kidding. Look at you. Look, you got uptight right away. You're like, Don't blame me for this. No, no, no, I didn't do this. One day, we're gonna get into your specific insanity. Boy. I really do appreciate you doing this. And, you know, I really, you know, I'm not going to keep saying it to you over and over again. But your amassed knowledge, and how much you've put into all this already in your life is really impressive. So I'd like to keep this podcast going for a long time so I can find out what else you do. I want to see what like 48 year old Julia does. I'll be like, can you talk louder because I won't be able to hear you right then. You'll be like why are these air pods not working? I'm like I don't know.

Huge thanks Julia for coming back on the show. Thanks to Omni pod for sponsoring thanks to the Contour Next One blood glucose meter for sponsoring and thanks to touched by type one. Now you can check out touched by type one on Facebook or Instagram and of course at touched by type one.org check to see if you're eligible for the free 30 day trial of the Omni pod dash and Omni pod comm forward slash juice box and get yourself more information about the Contour Next One blood glucose meter or get started today. At Contour Next One comm forward slash juice box you may be eligible for a free meter.

Supporting the show is as easy as sharing and subscribing subscribing the podcast app you're listening to share with someone who you think might enjoy the show. you support the show. I'll do the rest

Please support the sponsors

The Juicebox Podcast is a free show, but if you'd like to support the podcast directly, you can make a gift here. Recent donations were used to pay for podcast hosting fees. Thank you to all who have sent 5, 10 and 20 dollars!